Above is a screenshot of my post at The Conversation. Below is a fuller and earlier version:

A few weeks ago I made a long-anticipated pilgrimage to The Museum of London to visit The Crime Museum Uncovered; anticipated because, for the last 11 years I have curated another police museum, and the dilemmas of keeping and displaying contentious artefacts and documents interests me; in addition I am a PhD student at the Open University examining the material culture of police archives.

Tourism gone dark

Tourism is defined as dark when it involves visiting sites associated with death, disaster and tragedy “for remembrance, education or entertainment” (Lennon and Foley, 2000). It isn’t hard to find examples of independent museums who make no bones about exploiting their darker sides. Just think of The Clink or The London Dungeon. But the outrage over the recently opened Jack the Ripper Museum in London (also see my earlier blog on the Jack the Ripper Museum) shows how controversial dark tourism can be and how easy it is to get wrong. This museum clearly intended to target particular visitors, and ignored the fact that the subject is much more complex, including a number of important concerns around womens’ rights, poverty and crime. As a small, ill-informed enterprise they crossed ethical boundaries.

These grey boundaries mean that the brand of dark tourism is something that the partners of this latest exhibition (The Museum of London, The Metropolitan Police Service and The Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime) have tried to distance themselves from. It’s obvious that they are anxious to avoid allowing visitors to unashamedly gawp at cabinets of curiosities and to ensure minds are correctly channelled. They do so by safely anchoring the exhibition around academic themes such as museology and historiography, and by linking each of the 24 cases featured to developments in crime detection or law. They are also keen to emphasise the need for discretion and respect for the victims: they exhibit no individual cases post 1975 and, as part of the ethical process of selection and in compliance with the Human Tissues Act 2004, they display no human remains. The police’s messages and outcomes are not as transparent. Undoubtedly it has been a huge public relations opportunity to celebrate their role in keeping the streets of London safe. In addition, however, remembrance is important and the display of a burnt riot shield from the Broadwater Farm riots of 1985 not only provides a far too small platform for contested histories, but also an opportunity for the police to remember and to remind the public of their fallen colleague, PC Keith Blakelock.

Spotting dark tourists

So, I asked myself as I sat in front of the panel about the Kray twins: what does a dark tourist look like? I considered the party of white-haired ladies who gathered in hushed discussion and who could, for all intents and purposes, have been Womens’ Institute members tutting over a disastrous sponge cake. The Kray twins were strange celebrity/gangster hybrids whose glamorous nightclubs served as portals through which the rich and famous were able to briefly pass, tasting a parallel world on the “other side of the law”. A form of reality dark tourism, perhaps?

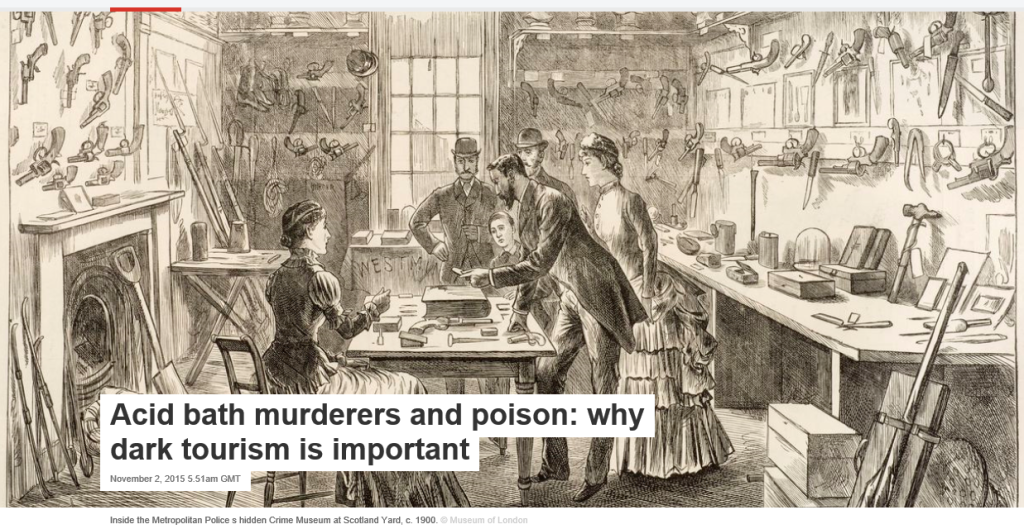

The original Crime Museum did something similar. Based in New Scotland Yard’s notorious Room 101, it indeed housed some truly horrific items and, because it was never intended to be a “museum”, but rather a training resource, it had no boundaries around ethics. The small space created a melting pot where men in shiny, squeaky shoes and creased trousers rubbed shoulders with celebrities, politicians, historians and potential criminals (in the visitors’ book for 1905 is the signature of Frederick Seddon, who later murdered Eliza Barrow).

In the past, dark tourism was everywhere. Now it’s tainted, something that major museums are keen to distance themselves from: modernity has separated us from the daily immediacy of death. Yet we still have a basic human desire to understand the incomprehensible and to push at our own ethical boundaries. As such, all museums play an important role in education, remembrance and entertainment and most hold numerous artefacts relating to death in some way. How many millions of visitors have stared at the grotesquely distorted figure of Lindow Man in the British Museum? Or the human-shaped voids at Pompeii frozen forever in the act of dying? Do such displays fall into the dark tourism net?

So the dilemmas, particularly for museums of crime, are around how to manage the boundaries between entertainment and the perception of profiting at the expense of others pain. Profit, though not touched upon in this exhibition or supporting material, can’t have been far from the Metropolitan Police’s mind: with the sale of New Scotland Yard and with massive cuts across all police forces this small museum is not a key aim or objective of the police and needs to earn its keep. In August 2013 the Express posited a similar thought: “If entrance was charged at £15, the exhibition could look to bring in up to £4.5m” (adult entrance is £12.50).

Despite this pecuniary background, correctly managed, dark tourism is actually quite light at the edges. When emphasis is placed on remembrance and education it is a healthy part of building on our life experiences and the term should not be shied away from. It’s important to engage with and talk about our fascination with death.

Some further reading:

Lennon, J. and Foley, M. (2000) Dark tourism: the attraction of death and disaster, London and New York: Continuum

Rogers, N. (2002) Halloween: from pagan ritual to party night, Oxford University Press

Walby, K. (2011) “The polysemy of punishment memorialisation: dark tourism and Ontario’s penal history museums”, Punishment and Society, vol. 13, No. 4, 451-475

Keily, J. and Hoffbrand, J. (2015) The Crime Museum uncovered: inside Scotland Yard’s Special Collection, I.B. Tauris

I enjoy writing these blogs – I hope you enjoy reading them; please do share or comment!